Our little warp research team has been making incremental progress towards reaching our goal of engineering an experimental setup. We discovered some mind-blowing concepts and some overlooked research.

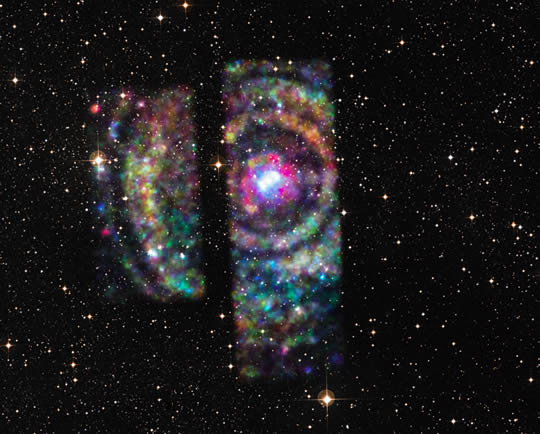

Image credit: X-ray: NASA/CXC/Univ. of Wisconsin-Madison/S. Heinz, et al.

In my previous post I outlined how Neutron Interferometers are a potentially viable instrument for measuring gravitational waves. We’re starting to get clarity on this concept. The COW experiments mentioned in that post focused on somewhat lower frequency gravitational waves - namely those coming from tidal effects on the earth. Because we’re observing a very localized warp effect, it’s possible the gravitational waves caused by a small experimental warp bubble may manifest as high-frequency waves. Consequently, using Neutron Interferometers to measure high-frequency gravitation may be a novel idea.

Following this idea, the research became more interesting. So I’ll separate this post into two main topics that are interrelated but interesting on their own.

Gravity Produces Light

There’s a developed field of research focused on gravitational waves producing light that dates all the way back to 1962 that eventually sparked physicists to do the math on relationships between electromagnetism and gravity. This is important to our research because Dr. White at Eagleworks NASA proposed using a toroidal EM device to induce a space-time warp. Finding an equation to help us exactly determine the gravitational potential of the EM field is key, since we need to plan how sensitive our interferometer will need to be in order to measure this effect. Luckily, research into Neutron Stars has given us some of the tools to explore this more properly.

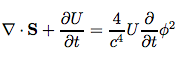

Time-varying gravitational potential induces electromagnetic radiation, see Preston Jones’ paper.

We’re using an equation by Preston Jones (see #21 in Electromagnetic radiation from temporal variations in space-time and progenitors of gamma ray burst and millisecond pulsars) to work backwards and understand the gravitational potential of an EM field. This is a Post-Newtonian approximation and when read the opposite way it means “electromagnetic radiation correlates to a time-varying warp”. This is complicated because a time-varying warp field is going to fluctuate and be very dynamic. If we use an experimental technique known as “lock-in” then we might literally lock ourselves of our own signal. Since the signal we’re seeking seems to be highly unstable, we need to understand how to work around this.

Our interest in this gravitational research triggered a tangent where we looked closer at the original 1962 paper above. Quoted directly, “From general relativity follows also the possibility of the inverse conversion of gravitational waves into light waves, but this problem is hardly of interest.” Um…wait? Did I just read that!?

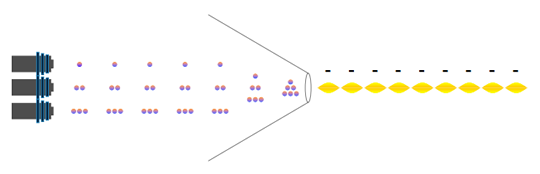

Quantum optical squeezing. Image credit: Eric W. Davis and H. E. Puthoff.

Now let’s work backwards and start tying some concepts together for some speculation. If gravitational waves can produce light waves, then there’s got to be a way to convert this back in the opposite direction. No idea how just yet, though two ideas may be applicable. The first is an idea propsed by Eric Davis in a paper called Experimental Concepts for Generating Negative Energy in the Laboratory. One of the concepts proposed in this paper is “quantum optical squeezing”, where photons being squeezed together will produce negative energy bursts. Remember that in the Alcubierre metric, negative energy is required to create a “warp bubble”.

The second idea is a lab experiment that shows photons can be grouped together. The Rydberg blockade is an effect where molecules can be frozen into “molecules” and was produced by a team from Harvard and MIT (see Attractive photons in a quantum nonlinear medium). The applications of this effect are not yet fully understood, though you could speculate this is a storage mechanism of photons.

Considering these topics together, there may be research of interest here to start looking at experimentation. If photons can be frozen and grouped together, there may be a technique to squeeze them. Currently, this is far beyond the scope of our immediate goals though it is of great interest.

Two Unresolved Areas of Gravitational Research

We’re already aware of using Neutrons to detect gravitational waves, but what about working with electromagnetism and using EM itself to detect high-frequency gravitational waves?

In another very interesting discovery, we realized that there is a line of research that looks into using EM to accomplish this very goal. There seems to have been renewed interest in this field as of the 2000s, including details in papers like this one and this one. Though not much seems to have been accomplished in this research, it does open the question as whether neutron interferometers can be replaced with an EM solution. It appears there are two inhibitors preventing this research from advancing:

2) The large cost of improving such EM equipment to bring it up to date.

This is far different than the line of Neutron Interferometer research that has proven to be more effective. What if the two fields started comparing notes? What would we discover?

Moving Forward

Unless we make more interesting discoveries, my next update will likely be our approximations for the actual gravitational potential of an EM source. Much work is needed to determine if this can match the sensitivity of a neutron interferometer, assuming we proceed with neutron interferometers as a primary measuring instrument.